HEIM TRIBUTES

On the Occasion of Winning the 2024 Rolf Schock Prize awarded by the Swedish Royal Academy

Marta Abrusa

A duct-taped banana, by Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, was sold recently for 6.2 million dollars. But few people know that the original artwork was created by Irene Heim in 2002, who during an Introduction to Semantics class taped a banana onto the whiteboard, in order to emphasise that a part of the semantic expression really referred to the object denoted. Congratulations Irene for this well-deserved prize!

With gratitude.

Sigrid Beck

Irene was – and is – one of my most important teachers. I was officially introduced to her by Arnim von Stechow during the time I was writing my MA thesis. This must have been in 1993, in a hallway of the University of Tübingen building I work in today. I was extraordinarily shy and completely in awe of such an important and impressive personage. Somehow, Irene brought it about that we were very quickly able to go over my data and talk about semantics in a fairly relaxed way. Discussing my ideas for an analysis with her felt like somebody was switching on a bright light illuminating a messy and dusty archive of boxes, shelves and cartons filled with bits and pieces of thought, and helping me to put things in order. It was also rather fun: I remember we had some good laughs on the way.

It is still amazing to me that Irene found the time and interest to talk to a young, tonguetied person with nothing to particularly recommend her. To me, this is a sign of Irene’s generosity, and also an indication of how purely scientific her approach is, with no importance attached to outside considerations.

I was lucky to be able to talk to Irene often in the early phases of my carreer. She was one of the advisers of my PhD thesis – at a time when email correspondence involved a line editor: I would carefully type one line, make sure that it said the right thing, press the return key, and compose the next line of my seven line email from Tübingen University to Irene at MIT. Even under such decidedly suboptimal circumstances, she helped me greatly to straighten things out. We all know that her clarity of thought and skills at logical argumentation far exceed other people’s, but perhaps not everybody knows that she is willing to be this patient for the sake of the kids.

To this day, Irene’s teachings regularly impact my work. For example, I will find myself jumping from data point to data point in delight, excitedly pursuing all the possibilities language opens up, to hear in my mind Irene asking “So what does that show?” – inviting me to stick to a logical line of argumentation. Or maybe I will read a paper that for some irrational reason I do not like so much, feeling tempted to simply discard the whole thing; but Irene will remind me to analyse what is and what isn’t compatible with my own evidence and to clarify my position. Sometimes when I teach, I try to take my inspiration from Irene’s work for how to simplify things without becoming obscure.

Irene has been a good friend for more than 30 years, although I will not write about that here.

For all this and much more, I thank her very much.

Elena Guerzoni

My congratulation to The Swedish Royal Academy of Science that awarded you the Schock Price, thus acknowledging at least part of your unparalleled impact in the filed of semantics…which, in my modest opinion, goes well beyond (!!!) the contribution for which the award was assigned to you. For what it’s worth, you have been my role model since 1998 and every year since I have become more aware of this.

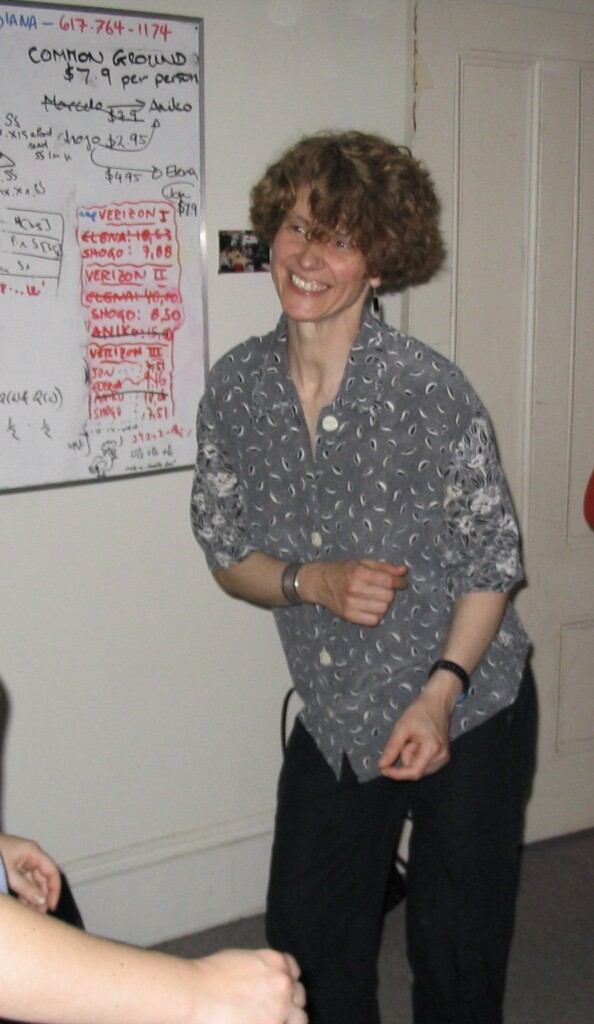

I am attaching a short video and some pictures from my defense and defense party.

The video is the result of an application of your intro to semantics motto “Simplify, simplify!” :).

The third picture is there because many might not know that you are also a beautiful dancer.

Hans Kamp

Dear Irene,

You and i saw each other close to a month ago for the event in Stockholm that is directly connected with the workshop on Dec. 7th. On that occasion I was among the witnesses to the many congratulations you received. I take the slot I am given here to add my congratulations to all those. This is also an opportunity to say something that for decades I could have said if I had only been a little more daring and inventive in creating the channel it needed: That I have been an admirer (and unobtrusive user and profiteur) of much that you have done since the time that Dynamic Semantics was a dominant shared and uniting interest for the two of us. In particular, there are the many insights you have had, and effectively communicated with the world at large, about adjectives. That goes back to the days when we were colleagues in the mid-eighties at the University of Texas. But it also includes much that came later for me, like your work on superlatives or the extraordinarily insightful things you have to say in the paper ‘Little’ (not so-called because of its importance). You told me in Stockholm that the Rolf Schock Prize had torn you out of genuine retirement. If you hadn’t, I would now say more about these deeply felt debts, and the impact they have had on more recent work of my own. But as things are, I leave it at this, hoping that perhaps there will be a time before too long when I can explain a little better why you have been so important to me all those many years.

Toshi Ogihara

I sincerely thank you for your semantics education you provided in Austin. Hope you are doing well.

Barbara H. Partee

Irene Heim was one of the outstanding semantics students who joined our PhD program at UMass Amherst in the early period when Emmon Bach, Terry Parsons, and I were leading a push to extend “Montague Grammar” and integrate it into linguistic theory, adding a real semantic component. That group of students who started in the 1970s included Robin Cooper, Muffy Siegel, Paul Hirschbühler, Rick Saenz, Ken Ross, Mark Stein, Irene, Elisabet Engdahl, Jonathan Mitchell, Mats Rooth, and Gennaro Chierchia. Irene had originally intended just to visit for a year and work with Emmon, me, and Terry, but she reports that she really liked the program and the people and the real critical mass of serious students and faculty working on semantics, and also liked phonology and syntax more than she expected, so she stayed to do her Ph.D., and she and we were really glad she did. Her dissertation was the first UMass semantics dissertation to build on a very Chomskyan syntax, which I think had a big influence on Chomsky’s attitude towards formal semantics. When I asked Noam a decade ago whether his attitude towards formal semantics had changed by the time you all hired Irene in 1989 he replied “No. Formal semantics had changed.” And I think that was an allusion to Irene’s dissertation. As Irene herself told me when I interviewed her, commenting on the environment she encountered at UMass and more generally in the US when she arrived in 1977, “either you were a syntactician who really didn’t know what a quantifier was, or you were a semanticist and you had to do categorial syntax or GPSG or whatever, and it just didn’t seem that the connections were that logical between these choices, and that was a point I wanted to make in my dissertation.” I really credit Irene and Angelika Kratzer with bringing formal semantics and Chomskyan syntax together, an effort I had begun in 1972 but had given up on after a few years in the face of both Chomsky’s resistance and the promise of monostratal theories such as the ones Irene mentioned. So to me, Irene’s greatest contributions include not only her many great works on semantic problems, but also her leading role in bringing syntax and semantics together and teaching and mentoring many of the younger generations of researchers at the syntax-semantics interface. The field is incomparably richer because of all she has done. (See also the slides (download) from a talk I gave at the “Going Heim” workshop at UConn in 2015.)

Philippe Schlenker

When I first visited MIT Linguistics in the mid-1990’s, I witnessed a clash of two cultures. Some of the bright young minds I encountered made a point of replying as fast as possible to anything they were told (sometimes a bit too fast for their own good). Others did the opposite: any answer was preceded by a long, and sometimes very long pause. While the former culture didn’t come as a surprise in an environment notoriously filled with wit, talent and ambition, the latter was a bit disconcerting at first. With time, I conjectured that the second group was unconsciously emulating Irene Heim: in appointments and seminars alike, she would pause (and sometimes look out the window) for as long as was necessary to come up with a complete, perfectly thought-out, beautifully articulated and invariably correct answer. As a result, pausing for truth became a local subculture.

Nor was this limited to academic matters. I was once the student co-organizer for a colloquium party hosted at Irene’s place. Since it was a bit hard to locate, I asked her for directions. There was no answer at first (a pause of sorts), but then a beautifully hand-drawn map came my way, complete with innumerable alleys, drives, lanes and courts. Irene apologetically explained that she had become “obsessed”, and thus taken days to complete this piece of art. I concluded that there were genuinely no bounds to her sense of detail.

What Irene did for her students, including me (and for my map), she also did for the field at large, through her written oeuvre (complete with her immaculate handouts), her teaching, and her advising: with exactly zero tolerance for vagueness, approximation and obfuscation, she took the time necessary to radically clarify and transform question after question in the study of meaning, invariably raising standards, and in effect turning entire areas of the philosophy of language into a rigorous science. This applied to semantics and its interface with syntax, but also to pragmatics, which she was instrumental in transforming into a formal field. One of her pedagogical mottos was ‘let’s compute’, which of course was possible only because the field, largely led by herself, had turned vague questions into computationally precise ones. In this, there was more than an echo (albeit a characteristically understated one) of Leibniz’s old dream that disagreements could be solved by computation (‘calculemus’).

Of course linguists and philosophers would have wanted Irene to never retire—as there are always new areas in need of radical clarification. But there are other fields as well, and Irene is well-known for her love of manual work and handcraft. I have no doubt that she is now bringing her characteristic skills and Gründlichkeit to any hobby she may lay her talented hands on. Should there ever be a Schock or Nobel Prize for roofing or gardening, we may have further causes for celebration.

Raj Singh

I will recount here a story of a meeting I once had with Irene which I think exemplifies what those hallowed meetings were like. As I often did, I went up to the whiteboard in her office and scribbled some incoherent nonsense hoping that she would see the signal in my noise and help me to extract it. This particular noise on this particular day had to do with trying to connect proofs in the sequent calculus and the proviso problem. After patiently waiting for me to finish, she went up to the board, corrected an error in my reasoning, and reconstructed my idea to something that at last was sound and coherent enough to be assessed for its potential. And then she said, gently, staring at the lines of proof we’d created: “Now that I see what you’re trying to say, it’s not very pretty.” And then we got to work to figure out what we’d learned from this exercise (there was always a lesson).

Meetings with Irene were sacred to me. Somehow, someway, she always saw with such clarity whatever nugget of insight there may have been in my idea and helped move me along to higher terrain than whatever I walked in at. A clean, well-lighted place equipped with noise cancellation. I cannot believe how lucky I was to have her as my teacher and my (co-)supervisor. I will forever cherish everything she has done for me, and for the field. I go back to her papers and her lecture notes whenever I feel like I need her help, and when I am struggling with an idea I try to imagine myself back in her office and I try to imagine what she might say if I could scribble my thoughts for her on the whiteboard. What I would do to turn those imagined worlds into the actual world, even if for just a few minutes.

Thank you, Irene, and congratulations for this well-deserved recognition!

(Here are three pictures from the mini-celebration we had in the department after I defended my thesis in August 2008. All three include Irene, and one of them has my entire committee (Danny, Kai, Irene, and Bob).)

Kenneth Wexler

I had hoped to celebrate in person at this conference honoring Irene for her supremely well-earned amazing award and, of course, for all the work over all the years before that, but sadly for me family responsibilities made it impossible. There are so many people attending who are better prepared than me to recount Irene’s technical achievements, that it makes no sense for me to do it, besides saying that any award, any claim about Irene’s achievements, comes as no surprise to me. I know how extremely gifted she is and how supremely well she has used her gifts. Let me just mention some small personal moments that help to illustrate the kind of scientist and colleague that she is.

As you all know, contemporary semantics has many virtues. As someone not trained in semantics, one of the illuminating things I found about it, doubtless too belatedly, was the exquisite objectivity and insight into describing interpretive phenomena. I was unused to such a way of working on meaning in natural language. I remember being a presenter at the 2 conferences that Hintikka, Moravcik and Suppes organized in the early 70s, where Montague presented his first paper (I think) on doing semantics in natural language, The Proper Theory of Quantification. Barbara explained it to us. One of the striking things about Montague and taking nothing away from his contribution, was that, although he had this major insight into how to represent natural language semantics, using certain types of logics, he seemed uninterested in any details, as if simply figuring out what the general type of logic was is sufficient. Linguists of course wanted more, and more soon appeared. Nevertheless I had never seen an exquisite level of concentrating on exact interpretation so ably brought off as in my interactions with Irene.

One small personal example. Irene and I decided to teach our first (of two) graduate courses on semantics and acquisition, hoping to ignite research in the field. One topic we included was the semantics of determiners. I was lecturing on those results and the standard famous interpretation, going back to Piaget, which said that children used the instead of a in certain contexts because children were “egocentric”, that is they couldn’t correctly follow what the speaker had established as a contextual set but instead picked their own context set from those available. There were several experiments. When I got to one of them, Irene jumped in, and said, no, that experiment can’t show that children are taking the wrong context set, because there is no context set at all that the child could choose. Although the girls and the boys are mentioned, there is no individuating information the child could use, not even a picture of the boys or girls, and certainly nothing in the discourse. So how could a child bring a particular boy or girl into focus, which would be required on the egocentric explanation.

I think it took me about a half hour to understand her argument, and I tried to argue back. But she was right. I had been in a dogmatic slumber, accepting what everyone accepted, not thinking analytically about experimental situations in real detail. What I learned from Irene went way beyond those experiments (though they provided a basis for ideas I developed about an alternative theory.) I learned how important it was to pay close attention to exact semantic phenomena, and how central that was to any semantic explanation. Standard practice for good semanticists I suppose, but I had learned the point from a master.

Think how unusual it was to have this type of collaboration, of patiently educating me and a class. In a field in which Irene had never worked. She used that brilliant mind wherever it was interesting and necessary. And was patient in letting her knowledge reach others slowly. In years after I saw her do the same in other areas of acquisition of semantics and contextual situations, including binding theory and others. What semanticist besides Irene has developed a theory of how children develop a certain analysis of verb phrases?

She didn’t dismiss the phenomena because they were in another field if approached narrow-mindedly. Whether in theory creation and analysis or empirical observation, the refined keenness of Irene’s brilliant mind is always at work.

I could say much more about her amazing influence and collegiality to things that are close to my heart. But I have gone on too long. Irene, thank you for your constant encouragement and patient teaching for so many scientists. What would we have done without you? Congratulations on your huge honor, acknowledgement of a life well-spent.